Carl John Erickson

Pre-WSC Background

It was not the beauty of the Columbia River that bends and weaves its way through the hills and chasms of Benton County, and it was neither the richness of the land nor the vast flowing landscapes that brought made Richland, Washington famous. In fact, it was the destruction of the tiny farming community of around 250 people in 1940 that made way for the Richland we all know today as the site of the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. As World War II raged on, the United States Army purchased 640 square miles of land that hugged the Columbia River, including the land on which the farming community of Richland sat. They evicted the residents of tiny Richland and constructed a whole new town to house the workers that built and maintained the nuclear reservation where the uranium for the first atomic bombs was enriched. The original town of Richland, Washington, and its native son in Carl John Erickson, sacrificed themselves so that their communities and country and its way of life could be defended. Carl John Erickson is one of only a few Fallen Cougars that lost both his hometown as he knew it, and his life in defense of his nation. It was that town and that community that made Carl the kind of man that laid down his life for others, and there is a type of poetry in realizing that his community did so as well.

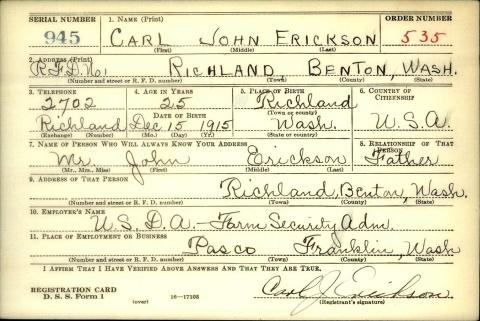

In 1893 John Erickson, who at that time spelled his last name “Eriksen” immigrated to the United States from Sweden. In 1905 a young woman named Hulda, also from Sweden, immigrated here as well. The two married and John became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1898, and Hulda in 1909. The 1920 census shows that Hulda and John settled in Horn Rapids, Washington, on the outskirts of the tiny town of Richland. Both Hulda and John spoke English, but list Swedish as a language spoken in the household. Their children, too, were bilingual like their parents. Hulda gave birth to their first child and only daughter, Eva Erickson in 1912, and their second child and only son, Carl John Erickson, in 1915. Carl was baptized Lutheran at the First Lutheran Church (built in 1904) in Kennewick, Washington. John owned his own fruit farm in Horn Rapids, and Hulda noted her profession as “housewife” tending to the myriad needs of a farm and household while raising her children. In 1930 Eva was 18 years old and Carl was 14 years old, still living on and working the farm in Horn Rapids. The whole family lists their primary language as English, but they had a new member of the household, a cousin of John’s, 18-year-old Ray who is listed as a laborer working on the fruit farm. After completing High School in Richland in 1933, Carl set out for higher education and enrolled at Washington State College, not far from his family and the farm in Pullman, Washington.

WSC Experience

There is precious little on Carl’s time at WSC. We do know that he majored in Agricultural Business, and he was in the Alpha Zeta fraternity on campus. Completing his Bachelor of Science degree in 1937, he is pictured in the Chinook yearbook along with the other graduates of 1937. The Spokesman-Review published an article noting the large class size for the WSC seniors of 1937 with the headline “Half a Thousand Up for Degrees,” and Carl Erickson is listed among those in agriculture department awaiting their commencement ceremony. Carl did not wait long to put his wonderful WSC education to work. In the 1940 census, Carl is back home in Horn Bluffs where he lists his employment with the Farm Securities Administration. The federal government under the FDR administration had been working tirelessly to install its New Deal programs. An attempt to jumpstart the American economy through government investment in everything from education to agriculture, from electrification to art and literature, many jobs were created for men with Carl’s talents. One of the New Deal “Alphabet Soup” agencies was the Farm Security Administration, designed to assist farmers in managing debts, growing market-appropriate crops, and stabilize the food industry. The Spokesman-Review ran an article on August 20, 1941 in which Carl is listed as an Associate Supervisor working on farmers debt relief, a topic that must have been near and dear to the farmboy’s heart. He made his way up North to Northport, in Pond Oreille County, Washington in December of 1941. The Spokesman-Review again covered some of Carl’s business in Northport where “County rural rehabilitation committeemen and farm security administration met here Tuesday. . . Robert H. Grant, district farm debt adjustment specialist, and Carl J. Erickson, county FSA supervisor, explained the objectives of their administration. Committees discussed the tenure program.” But, while Carl was putting his education to work for the betterment of rural communities and the farmers he no-doubt grew up with and understood, the world outside American borders was falling deeper and deeper into chaos.

Wartime Service and Death

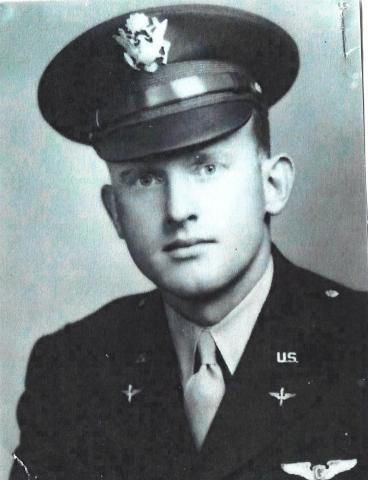

The Allied strategy to defeat the Nazi Empire called for attacking its “soft underbelly” as it was called, the outskirts and edges of Nazi German and Fascist Italian holdings. The first plan called for digging the German and Italian military contingents out of North Africa and opening up the Mediterranean to Allied shipping and aerial power before attacking the belligerent Axis powers directly. The Allied Invasion of Axis North Africa, codenamed Operation Torch, was planned and on May 14, 1942. Meanwhile, back in the states, Carl registered for the selective service. He was 25 years old in 1942, 5’9 tall, 165 pounds with a light complexion, blue eyes and blonde hair. He officially enlisted in the United States Army Air Corps on May 5, 1942 and was assigned the service number 39180534. A Spokesman-Review article on May 5th reported that the “selectees for Army Get Warm Send Off” and that the inductees “were served breakfast by the Legion and auxiliary and entertainment was provided by the high school band and choir. Leaving were Lawrence W. Deaver, Irvin C. Urmey, Carl J. Erickson, Herebert O.C. Malchow, Ernest C. Perkins,” and more.

On June 27, 1942, The Spokane Chronicle ran an article with the headline “Inductees Ready for Army Service.” The article stated that “Inductees reporting at the Spokane induction center this morning numbered 106,” a number that included Carl.

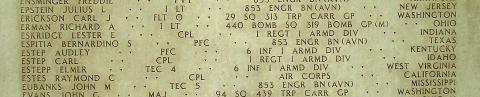

The Spokesman-Review kept tabs on Carl as he moved through the training process. An article on August 16, 1942 reported that “according to information received from the war department, private Carl J. Erickson has enrolled as a glider pilot student in the air force training detachment at Twenty=Nine Palms, California. Upon completion of the training course the student will be made a staff sergeant.” On January 8, 1943, one last article before Carl’s deployment was published in the Spokane Chronicle entitled “White Bluffs Man Glider.” The article reported that “Carl J. Erickson writes that he is in the last phase of training as a glider pilot at Dalhart, Texas. The new gliders will carry 15 men, he writes.” Carl was commissioned as a Flight Officer, assigned to the 29th Squadron of the 313th Troop Carrier Group, part of the 9th Air Force. Flight Officer Erickson was based in North Africa in May of 1943 where he would fly gliders attached to C-47 and C-53 cargo planes in what were called “Sky Trains” carrying troops and vital supplies throughout war-torn Europe. Erickson was likely involved in the dropping of paratroopers in Sicily in July of 1943 before the unit was assigned to transporting supplies and evacuating wounded soldiers from combat zones. The Air Trains took a lot of anti-aircraft fire from German and Italian anti-aircraft guns and naval vessels in the Mediterranean, but in the end, this was not what cost Carl John Erickson his life.

On October 12, 1943 another airmen named Archie McDaniel was the Crew Chief on one of the many transport missions that the unit engaged in. Flight Officer Erickson was piloting CG-4A Haig Glider being towed by a tug rope by a C-47 skytrain. 60 miles from Algiers the pilot and co-pilot of the C-47, Dwight E. Crist and Richard E. Loomis, towing Erickson’s glider flew through a broken cloud when they felt the glider behind them tug three times and then come loose from its rope. The C-47 lurched forward when the glider was cut free, and they lost sight of it in the clouds. Crist and Loomis dove down to try and get a visual on the glider but could not find it. While they were listed as missing for some time after the accident, both Flight Officer Erickson and Crew Chief McDaniels were killed on May 12, 1943, flying over the Mediterranean.

Postwar Legacy

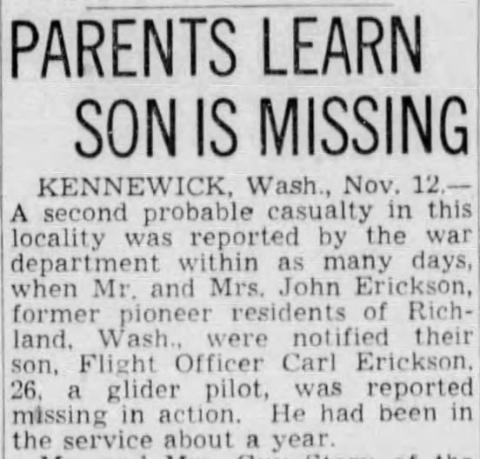

In November of 1943 the Erickson family were notified that their son was missing in action in the Mediterranean theater of War, the news hit the Spokesman-Review on November 13, 1943 “Parents Learn Son is Missing” was the headline. “A second probably casualty in this lovality was reported by the war department within as many days when Mr. and Mrs. John Erickson, former pioneer residents of Richland, Wash., were notified their son, Flight Officer Carl Erickson, 26, a glider pilot, was reported missing in action. He had been in the service about a year.” Back in Pullmen, WSC President E.O. Holland set about honoring those WSC men that lost their lives in defense of their country. He allocated funds to producing memorials for each of the fallen cougar men, and stayed in contact with the families, sending them memorial materials and offering comfort in their grief. This project is a continuation of what Dr. E.O. Holland began all those years ago. It is a memorial for the twenty-first century meant to ensure that Dr. Holland’s pure wishes are carried out for a new generation to remember the sacrifice of men like Carl Erickson. But this is not his only memorial. Tragically, Carl’s body was never recovered from the Mediterranean, so his name is inscribed on the North African American Cemetery and Memorial in Carthage, Tunis, Tunisia (memorial ID 56246827). His name is also emblazoned in golden letters on the World War II memorial at his alma mater, now called Washington State University, in Pullman, Washington. His name sits alongside all the other Fallen Cougar men who, despite everything, offered their services and sacrificed their lives so that the cougars of tomorrow, my generation and others, could live free.